How Imprisoned Dads Are Using Bedtime Stories To Connect With Their Kids

By Rob Kemp for The Telegraph

“I honestly believe that if it wasn’t for the stories I’d recorded for my daughter, Maisie and I wouldn’t have the strong a bond we have now,” explains Billy*, a soldier given a six-year prison sentence at HMP Dartmoor following his part in a fight during a night out on leave. “The stories I read to her from prison have kept me in her mind and in her life a lot more than visits alone would have done.”

Following his conviction in 2012, Billy split with his partner – Maisie’s mum – and feared that through losing contact with his little girl she would forget about him completely.

At Dartmoor – one of 100 prisons now operating the Storybook Dads scheme – Billy was offered the chance to record bedtime stories for Maisie onto DVDs that the charity then forward to Billy’s mother. She in turn would play them for Maisie.

“Our granddaughter was just 15 months old when her daddy was sent to prison,” explains Maisie’s grandmother. “We all worried that he would fade from her memory. There were visits of course, but often with big gaps between them. But the stories helped keep him fresh in her mind and so, when they do get to see each other, there is no shyness or reticence because she sees him often on TV telling her stories.”

Maisie is one of over 20,000 annual beneficiaries of the non-judgemental charity scheme first set up by a prison visitor, Sharon Berry, at Dartmoor prison in 2002.

Over 200,000 children each year are affected by parental imprisonment - more than are affected by divorce - and around 50 per cent of imprisoned parents lose contact with their families.

But research has shown that those who manage to maintain regular family contact during their prison sentence are up to six times less likely to reoffend.

“It provides them with the opportunity to be a father within the confines of the prison walls,” explains Sharon Berry.

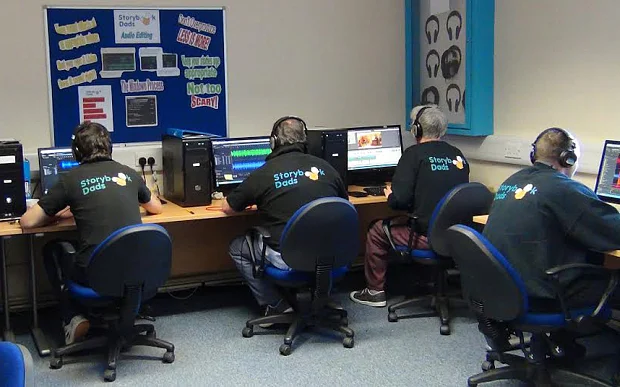

For the Storybook Dads scheme, the men select and read a favourite children’s book to camera in a ‘reading room’ within the prison. There are also puppets and toys they can use to help being stories to life.

“It’s really weird at first, sitting there reading a story to camera with a toy monkey on your shoulder,” explains Dexter, an inmate at Dartmoor. “But it’s a brilliant idea. My little girl had been having problems sleeping and the DVD I made has helped her cope with me not being there.”

The scheme now has 16 editors working across two editing suites based in HMP Dartmoor and HMP Channings Wood. According to the charity's website, over 5,200 audio CDs and 431 DVDs were produced in 2013.

Such is its success that Storeybook Dads has been taken up by servicemen and women in the RAF and Royal Navy on duty in the Middle East and beyond. Inmate editors have trained members of the Armed Forces in the recording and editing techniques so that service personnel can read their children bedtime stories too.

More recently, the scheme has been established in nine women’s prisons in the UK and also inspired similar programmes in Australia, Canada, Denmark and Poland.

Illiterate inmates are also able to record an audio book CD by listening to a recording line-by-line and repeating.

The process of creating stories has also helped inmates develop skills useful to finding work when they’re released. “When I was in Dartmoor I applied for a job with Storybook Dads,” explains Tony, 26, a former inmate. “My work record in prison wasn’t very good - but they took a chance on me and I worked there for over a year.”

Tony became an audio editor, learnt how to use a computer and then moved on to DVD editing. Like many men who’ve taken part in the process of reading, performing and editing stories, he developed his writing skills and improved his confidence and literacy. “Crucially it helped me keep family ties that would’ve been lost and kept me out of trouble on the wings as I’d concentrate on my future.”

Now the scheme has developed a new, more interactive Me & My Dad project, aimed at prisoners with older children. “Prisoners create Memory Books, where dads and their children fill in activity sheets where they learn about each other’s likes, interests, habits and daily activities,” explains Berry.

The prisoner then binds the completed pages in to a book which is then posted to their child. Other activities include craft DVDs (where Dad makes something step-by-step on camera), comics (where the child is often the main character in the story) and personalised calendars.

Billy has now moved to a lower category prison to serve out the remainder of his sentence. “I was granted a home leave from my new prison last week. I was expecting Maisie to be a bit shy around me but she was the complete opposite,” he explains. “We went round to my mum’s for breakfast. I asked Maisie if she wanted the TV on, she says ‘I want DVD, I want ‘Going on a Bear Hunt’ which is a Storybook Dads one I did for her.”

Billy and Maisie watched him read the story twice in a row. “I was cringing at my own voice and goofy expressions, but we were both laughing and it was great to see how much she liked it. Those stories have kept us together.”

* The names of the inmates featured have been changed for this article

For more information, visit storybookdads.org.uk